Kiyoko’s Story

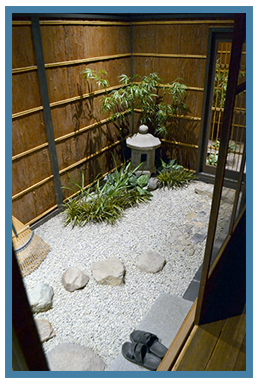

Kiyoko Ishiyama’s family owned the Japanese house that was given to Boston. Kiyoko did not actually live in our Japanese House, but her aunt and uncle did and she visited them often. Her own home was also a machiya-style home, very similar to ours, with a shop in the front and a living area in the back. Today, Kiyoko is a master Japanese calligrapher and watercolor painter. Through her art, she shares her memories of growing up in the 1940s and 50s in a machiya in the Nishijin neighborhood where our Kyo no Machiya came from. Scroll down for her story.

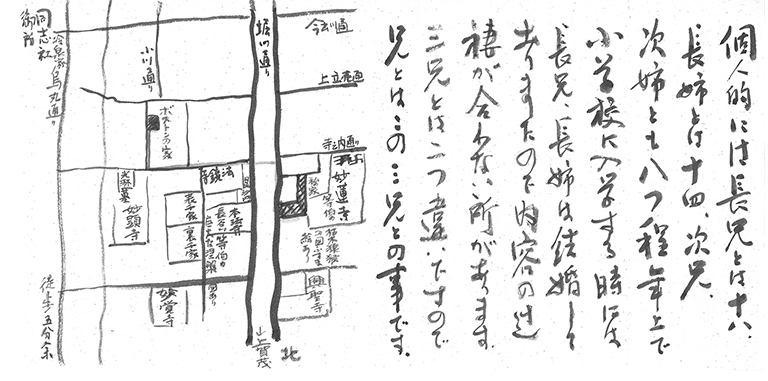

While I was growing up, my family, my relatives, and my neighbors – practically everyone - was working for the silk business in some way. Today, people no longer wear kimono as often, so as demand declined and so did the Nishijin silk industry. Many machiya houses where silk artisans and merchants lived and worked disappeared, replaced by modern buildings and wider streets. Yet, while wandering around the very small, narrow back streets in Nishijin, I still find myself hearing the sounds of the silk looms.

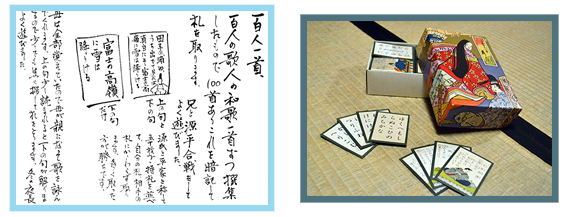

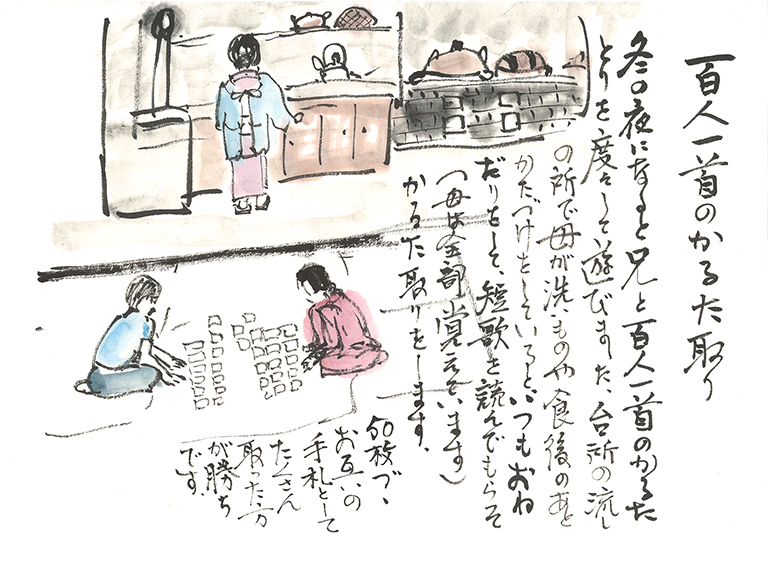

Each player has a set of fifty cards with poems printed on them. The players compete to be the first to find the card that matches the poem that is being recited. Whoever collects the most cards wins.

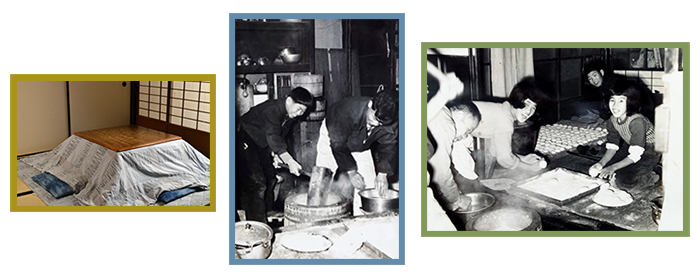

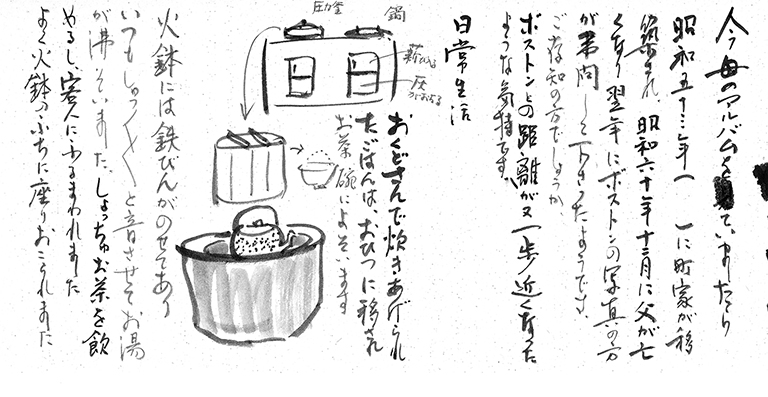

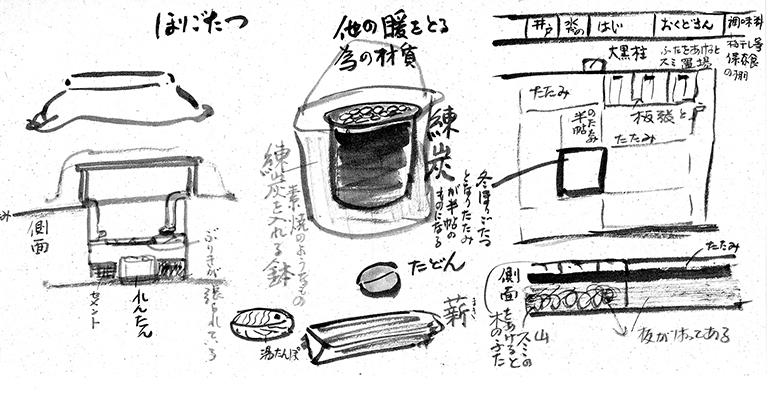

In winter, we often used a hibachi, or portable brazier. An iron kettle was set on top of the brazier, and the hot water always made a “shuu shuu” sound when it bubbled up. We often made tea for guests to drink. I liked to sit on the warm edge of the hibachi, which made my family angry and afraid for my safety.

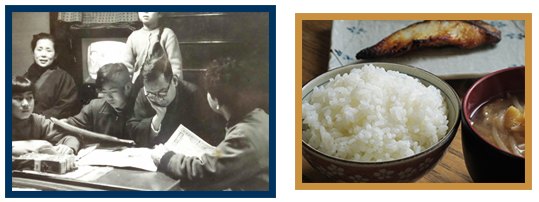

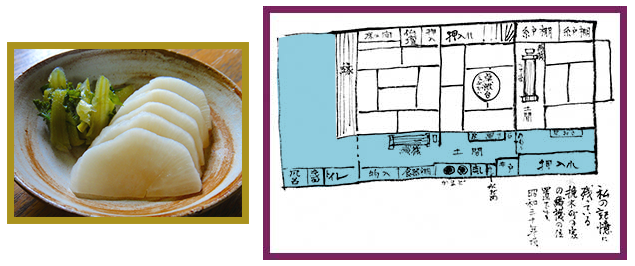

Dinners were fun but also formal affairs, where we children learned our best table manners. We all sat in seiza-style, with our legs folded under us. Our father sat at the center and made sure that we behaved properly.

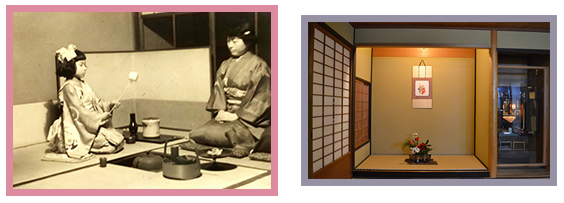

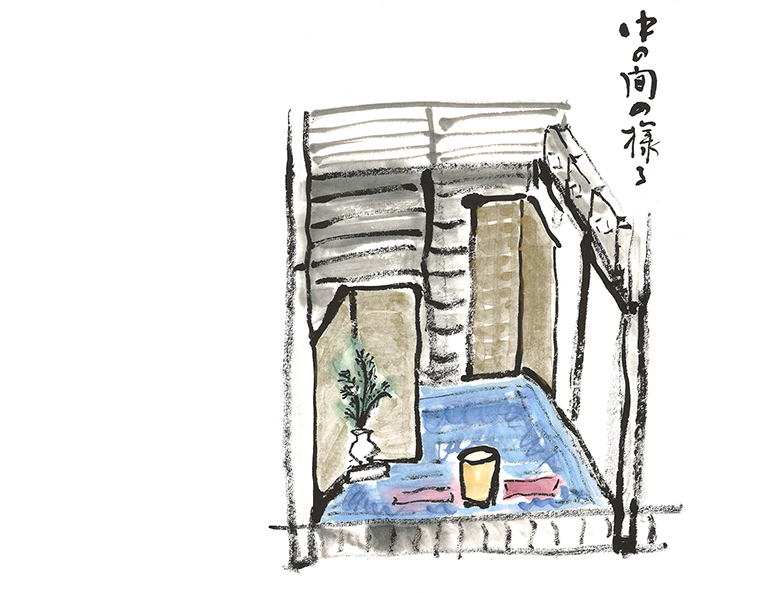

Even though my parents were very busy with work, they always found time for the traditional arts: chado (tea ceremony), ikebana (flower arrangement), and shodo (calligraphy). On very special occasions, our noh music teacher practiced with us in our house. Our tokonoma alcove was always decorated with seasonal flowers and special paintings.

Our family had many ways to keep warm. I used to sit with my legs under a heated kotatsu table to keep warm while studying. We used charcoal burners for heat, not electricity, because it was not common back then.

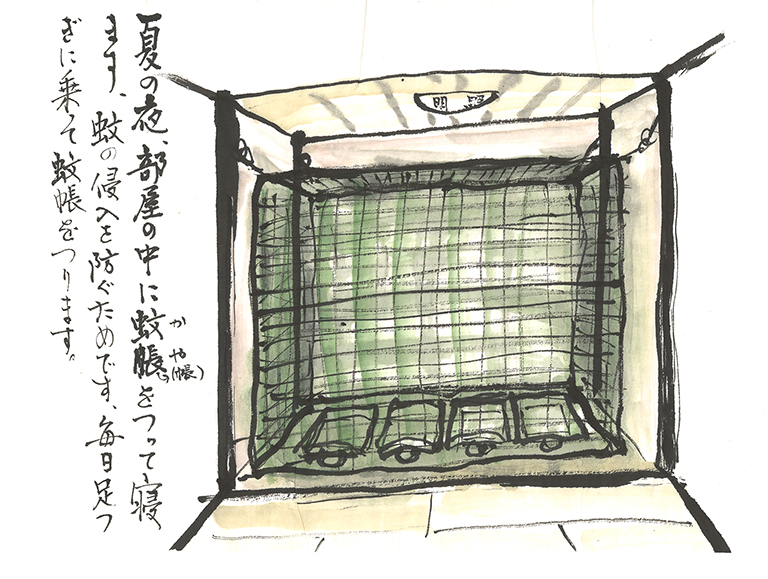

In the summer, Kyoto is hot and humid. At night, we used to set up nets to keep the mosquitoes out while still allowing a little airflow. We all played games and slept under the mosquito nets. It was like sleeping in tents inside our house.

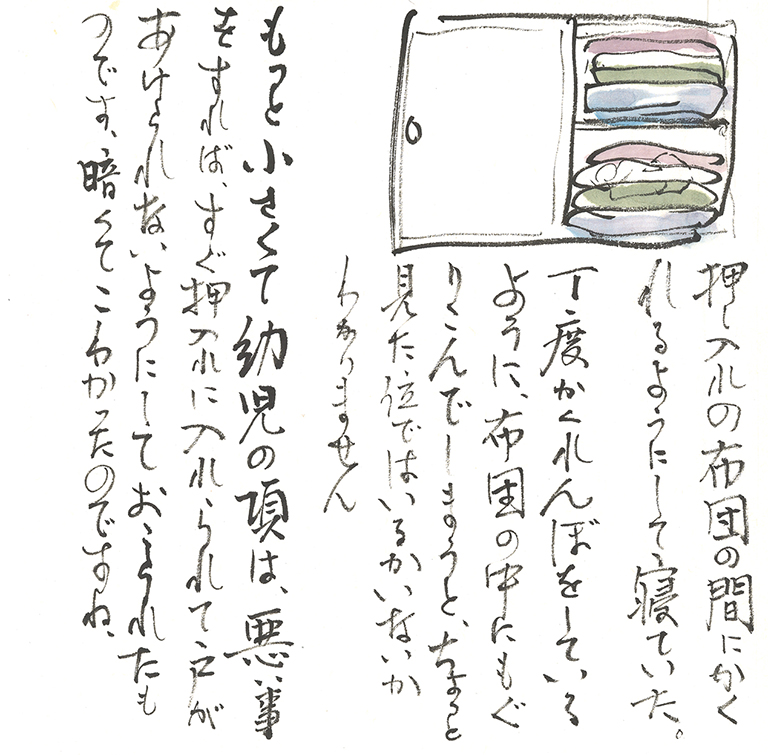

One time, I fell asleep while hiding between the futon blankets in the closet. I slept through the afternoon. When it came time for dinner, everyone thought I was missing, so they went to look for me. When I finally woke up and came out of the oshiire, my parents, though relieved, scolded me. I remember that incident very well.

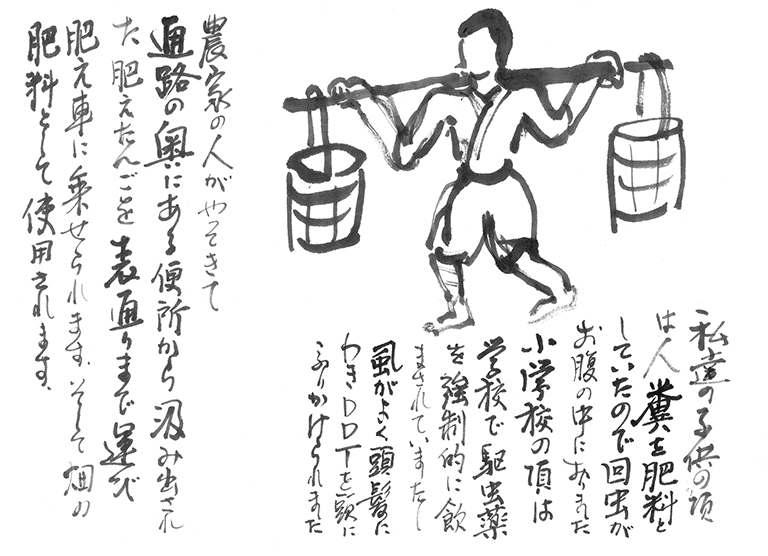

I remember that farmers used to come by to collect the waste from our outhouse to make into fertilizer. They even left fresh vegetables as a thank you payment.

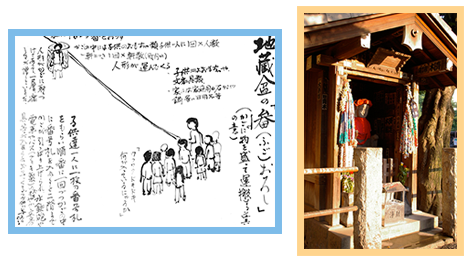

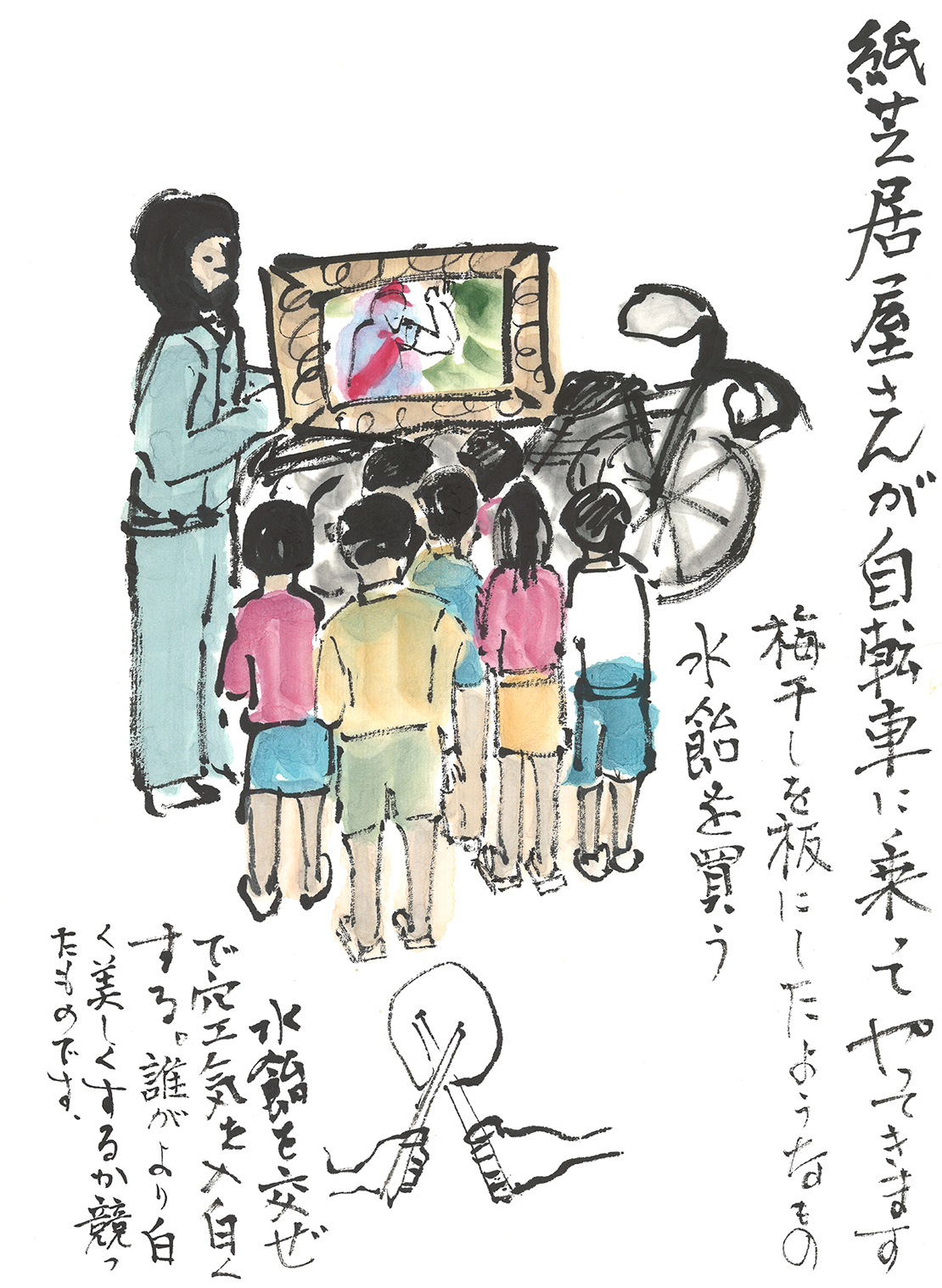

Kamishibai (literally “paper drama”) is a traditional form of storytelling that uses illustrated scenes to tell a story. Kamishibai was a popular form of entertainment during my childhood until television became widespread in the 1960s. The traveling kamishibai storyteller came to our neighborhood to sell candies and tell stories, using a wooden stage to display the pictures for the story.

One time, we stole persimmons from a tree at one of the temples. And we were caught by a Buddhist monk! He tried to scold us but he was really bad at it because he was so kind. Everyone in the neighborhood looked out for us and tried to keep us out of trouble, even if they were not our own parents.

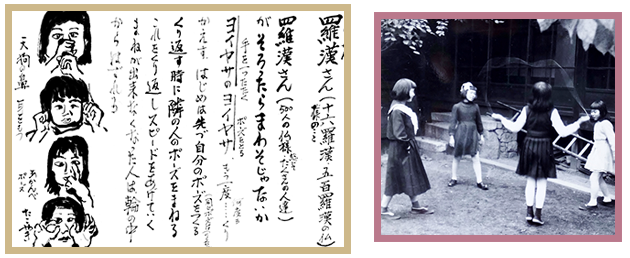

Jizo-bon is usually held on August 23rd or 24th, and each neighborhood has its own Jizo-bon festival. While a Buddhist monk chants scripture, neighborhood children, seated in a circle, pass around a large string of juzu beads —one bead at a time—to pray to defend themselves from illness and all types of disaster.

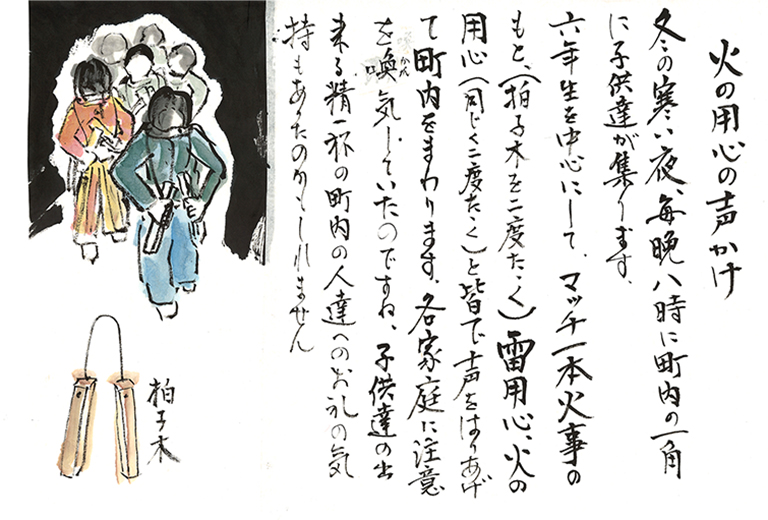

On cold winter evenings at 8 o’clock, neighborhood children gathered at a street corner. Mostly 6th graders, these children took hyoshigi wooden clappers, walked around the neighborhood and chanted “A single match can cause a fire”—clap, clap—“Caution to lighting and caution to fire”— clap, clap, to remind people to take care of the fire. It was something that young children did to help and to be part of the community.

When the neighbors lit candles for the lanterns to show respect for the deceased, it was the time for “Bon-odori” dance. Chochin lanterns were attached to strings and hung along the houses. At the center there was a tall podium where the drummers played music and people young and old gathered and danced. They shouted: “A fool who dances and a fool who just watches, if you both are fool, it’s better to dance.” Everyone from the neighborhood brought food to share, and we danced all night long!

We are deeply grateful to Kiyoko for sharing her personal memories in such a vivid, artistic and

evocative way. She has brought the story of our treasured Kyo no Machiya to life in a way we could not

have imagined. We are also thankful to Setsuko and Frank for connecting us with Kiyoko.